When making an Indie 19th Century Supernatural Horror game in the 21st Century, one name will loom over your project. Amnesia.

Designed under the working title of “Lux Tenebras” by Frictional Games, the Psychological Horror “Amnesia: The Dark Descent” exploded onto the Indie-Gaming scene in late 2010, growing a cult following and earning a reputation for gripping plot, immersive and genuinely tense and frightening gameplay. The internet became swamped with “reaction videos,” reviews and frightened playthroughs. Thanks to an eerie soundtrack, nausea-inducing visual cues, psychological tricks and a helpless, extremely vulnerable player character whose fear of the dark leads to interesting and innovative gameplay elements, the game was a huge success, drawing in players of all types wishing to test their mettle against one of the most frightening games of the past 5 years.

Amnesia received almost universal critical acclaim, winning several awards including “Excellence In Audio” and “Technical Excellence” at the 2011 Independent Games Festival. Featuring excellent voice acting, lush if slightly crude environments, rich historical context and a tense atmosphere, it was everything I love in video games, albeit on a budget. Had Frictional had more capital to spend, one can only imagine how the game would have looked.

When designing our game, we had to contend with being developers in a “Post-Amnesia” age. The art style, period setting, and desired gameplay style (puzzles, no combat, diary logs etc.) instantly squared us up against Amnesia. Initial attempts to deliberately avoid elements used in Amnesia simply proved to the detriment of our own production, so instead of consciously working toward or away form it, we simply acknowledged it’s existence without worrying too much.

Of course, you can’t blame us for our concerns. Our vision for our game; a 19th century Castle/Manor set in a dark, mountainous forested region, full of dark spaces, strange artifacts and frightening occurrences, has much in common with Frictional’s Amnesia. Our choice of setting and period gave us a chance to study and analyse Amnesia- not to do so would be foolish indeed.

As an indie-developer, Frictional budget was fairly limited to much higher profile games, but 21 months after it’s release, it had sold 1.36 million copies through multiple retailers (source: http://www.bit-tech.net/news/gaming/2012/09/12/amnesia-reaps-production-costs-tenfold/1), earning more than ten times it’s original budget of $360,000. Much of it’s success can be attributed to a combination of it’s immediate online following, and the critical acclaim levelled by both professional and amateur critics.

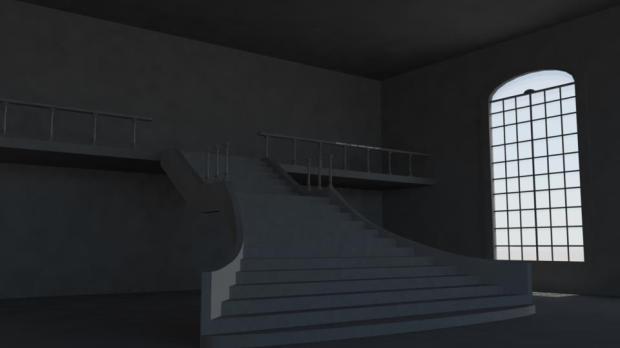

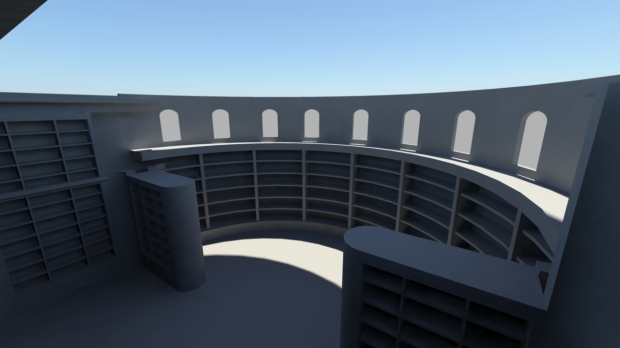

Following my study of its gameplay and design, two things that stood out were the attention to detail and simplicity of the design. As 3D Modeller on the Babel Project, it was my job to try and produce the game to a high standard, without producing overly complicated models that would compromise the performance of the game on lower end machines. Amnesia’s main selling point is a frightening, tense and immersive environment, which it pulls off with a surprisingly basic skeleton; many of the models are very simple, with texture mapping conveying a level of detail not present on the model itself. Lighting is sparse and moody, casting much of the game in shadow, while ambient sounds and discordant growls and thrumming bass notes maintain a sense of unease throughout the game, broken only by calming orchestral strings when reaching a “safe zone” or completing a puzzle. Looking at this, we realised that we could rely heavily upon textures to get away with the period detail and believable setting, allowing us to focus on gameplay elements and interactivity (sadly a focus we were unable to maintain during the project).

Additionally, as Art Director, I was able to examine the accuracy and detail implemented into Amnesia; everything in the game “fits” especially as the castle the game is set in is designed to varying degrees, incorporating 17th century stonework and architecture, and 19th century furniture and scientific equipment. Everything in the art department enriched the game and helped make it feel rich and believable which was a huge part of the games appeal, and helped contribute to the genuinely frightening atmosphere the game generated.